| A breakthrough in the design of molecular motors |

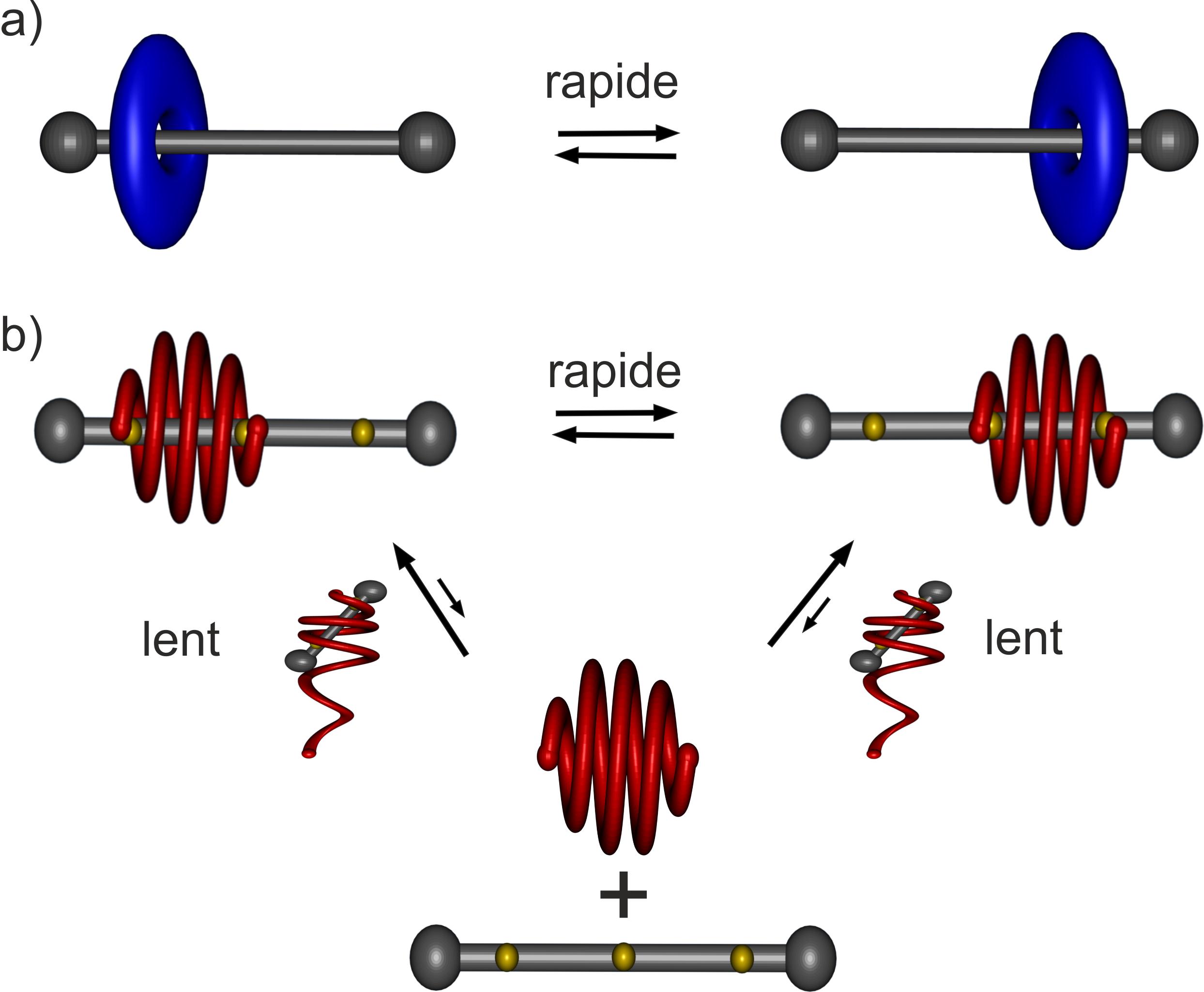

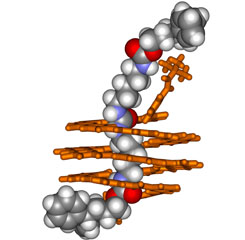

IECB team leader Ivan Huc, in collaboration with a Chinese team from the Beijing National Laboratory for Molecular Sciences, have developed the first molecular piston capable of self-assembly. Their research represents a significant technological advance in the design of molecular motors. Such pistons could, for example, be used to manufacture artificial muscles or create polymers with controllable stiffness. These results were published on the 4th of March 2011 in the journal Science. Living organisms make extensive use of molecular motors in fulfilling some of their vital functions, such as storing energy, enabling cell transport or even moving about in the case of bacteria. Since the molecular layouts of such motors are extremely complex, scientists seek to create their own, simpler versions. The motor developed by the international team headed by Ivan Huc, from IECB (CNRS/Université de Bordeaux, UMR5248), is a “molecular piston”. Like a real piston, it comprises a rod on which a moving part slides, except that the rod and the moving part are only a few nanometers long. More specifically, the rod is formed of a slender molecule, whereas the moving part is a helix shaped molecule (both are derivatives of organic compounds especially synthesized for the purpose). How can the helicoidal molecule move along the rod? The acidity of the medium in which the molecular motor is immersed controls the progress of the helix along the rod: by increasing the acidity, the helix is drawn towards one end of the rod, as it then has an affinity for that portion of the slender molecule. By reducing the acidity, the process is reversed and the helix goes in the other direction. This device has a crucial advantage compared to existing molecular pistons: self-assembly. In previous versions, which take the form of a ring sliding along a rod, the moving part is mechanically passed onto the rod with extreme difficulty. Conversely, the new piston is self constructing: the researchers designed the helicoidal molecule specifically so that it winds itself spontaneously around the rod, while retaining enough flexibility for its lateral movements.

a) Permanent assembly of a ring sliding along a rod b) Reversible assembly of an helix which spontaneously winds itself around the rod and then performs lateral moves By allowing the large scale manufacturing of such molecular pistons, this self-assembly capacity augurs well for the rapid development of applications in various disciplines: biophysics, electronics, chemistry, etc. By grafting several pistons together end-to-end, it could be possible, for example, to produce a simplified version of an artificial muscle, capable of contracting on demand. A surface bristling with molecular pistons could, as and when required, become an electrical conductor or insulator. Finally, a large-scale version of the rod on which several helices could slide would provide a polymer of adjustable mechanical stiffness. |

2, Rue Robert Escarpit - 33607 PESSAC - France

Tel. : +33 (5) 40 00 30 38 - Fax. : +33 (5) 40 00 30 68